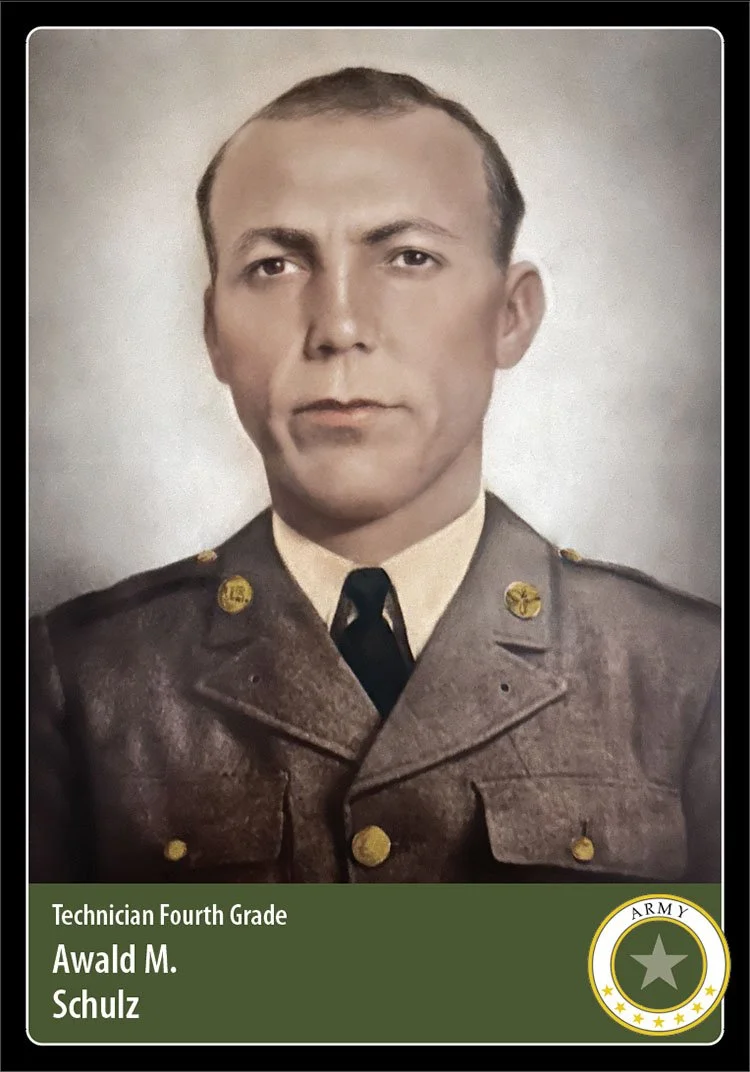

Hero Card 276, Card Pack 23 [pending]

Photo (digitally restored) provided by the family.

Hometown: San Antonio, TX

Branch: U.S. Army (Air Forces)

Unit: 440th Ordnance Company (Aviation), 19th Bombardment Group (Heavy), V Bomber Command

Military Honors: Prisonor of War Medal, Purple Heart

Date of Sacrifice: September 7, 1944 - KIA at sea, off the coast of Mindanao, the Philippines

Age: 26

Conflict: World War II, 1939-1945

In the final year of the “war to end all war” (World War I, 1914-1918), Awald Max Schulz was born on the 4th of July to Emil and Louise Schulz.

Awald was one of eight children—older siblings Amanda, Fritz, and Robert, and younger siblings Laura, Emil, Lola Mae, and Rosa. Both parents were first-generation German immigrants. Emil worked as a carpenter while Louise tended to the large family at home.

The family lived in San Antonio, Texas, where Awald attended Harlandale High School. As a young man, he worked as a carpenter before enlisting in the United States Army in July 1941, at the age of 23, at San Antonio’s Fort Sam Houston.

At the time, war was again raging in Europe and across Asia. Americans’ sentiment was strong that they should not get dragged into another deadly conflict in a foreign country.

Schulz was assigned to the 440th Ordnance Company (Aviation), 19th Bombardment Group (Heavy), V Bomber Command.

He’d eventually advance to the rank of technician fourth grade, or “tech sergeant.” The Army needed skilled tradesmen and created new ranks and pay grades for those with special skills.

War on the Horizon

In 1941, the use of air power in war was evolving rapidly. Gen. George C. Marshall established the Army Air Forces (AAF) on June 20, 1941—just a few weeks before Schulz enlisted. Not until 1948 would the United States Air Force become an independent branch of the military.

Schulz’s 440th Ordnance Company was responsible for the supply and maintenance of the 19th Bombardment Group’s heavy bomber aircraft.

With a hostile Imperial Japan invading and controlling countries in the Asia-Pacific region, the American War Department made plans to develop airfields in the Philippine Islands. Formerly a colony of Spain for three centuries, by 1941 the Philippine Islands had been a possession of the United States for four decades—through a treaty with Spain that ended the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Schulz’s 440th sailed from San Francisco, California, aboard the transport ship USAT Willard A. Holbrook. In a letter to his younger sister, Laura, dated Nov. 1, 1941, Schulz described arriving at Clark Field in the Philippine islands:

I didn’t get sick on the boat. But a lot of the boys did. I never was so glad to get off one place as I was when we got off the boat. They had us in there like rats. We was going to get off in Guam but they didn’t let us. We stayed on the boat for 20 days. I always wanted to be a sailor but not no more.

He went on to describe life at Clark Field, located 60 miles north of Manila, the Philippine capital city on the island of Luzon:

This place is so hot you can’t even wear any clothes. It [sure] is nice at night with the moon shining…So one of these days I am going to get a three day pass and go to all the islands here. I am going to have a good time while I can. I am making 30 dollars a month now but in this [Philippine] money I make 60 Peso. We can have a lot of fun on that much. But I am going to send you some money every month to keep until I get out of the Army. We get cloth here and have everything [made] to fit us. And you can buy a monkey for a dollar and a half. But we can’t keep pets on the post.

Surprise Attack

A month after Schulz arrived in the Philippines, America was at war. The Empire of Japan successfully staged a surprise attack on America’s Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Word of the attack came to Schulz’s unit an hour later, through local radio reports. Nine hours after Pearl Harbor, Japanese planes hit Clark Field in the Philippines. It’s unclear where T/4 Schulz was located at the time. Some of his 440th had been moved to the remote Del Monte Airfield in Mindanao—a new air strip carved out of a Del Monte pineapple plantation in the fall of 1941.

Defense and capture

For the next three months, American and Filipino troops attempted to defend the airfields from Japanese invaders. Schulz’s 440th was pushed south into the island of Luzon’s Bataan Peninsula.

Undersupplied and far from reinforcements, the Battle of Bataan came to an end when the Americans surrendered on April 9, 1942. What followed was a tragedy that would come to be known as the Bataan Death March. 60,000-80,000 Filipino and American prisoners of war were forced to march 65 miles through tropical conditions, without adequate medical care or food. Besides starvation and harsh conditions, prisoners were brutally beaten and killed.

T/4 Schulz would survive the brutality and be sent to Prisoner of War Camp #2 near the city of Davao on the Philippine Island of Mindanao. He lived long enough for his family to be notified that he was alive in the POW camp.

Hell Ships

The Japanese navy requisitioned merchant ships to transport prisoners for internment on the Japanese Home Islands. The prisoners of war called them “hell ships.” According to the Naval History and Heritage Command:

The holds were floating dungeons, where inmates were denied air, space, light, bathroom facilities, and adequate food and water—especially water. Thirst and heat claimed many lives in the end, as did summary executions and beatings, yet the vast majority of deaths came as a result of so-called “friendly fire” from U.S. and Allied naval ships, submarines, and aircraft.

T/4 Shulz was a prisoner aboard one such “hell ship,” the cargo ship Shinyo Maru, on September 7, 1944. Weeks earlier, a Japanese message was intercepted that led American intelligence to believe Shinyo Maru would be transporting 750 Japanese troops.

The submarine USS Paddle (SS-263) attacked the unmarked Shinyo Maru, not knowing it was filled with American prisoners of war. Paddle’s torpedoes sent the Japanese vessel to the bottom of the sea, along with some 750 American prisoners of war—including T/4 Schulz.

When POW Camp #2 at Davao was liberated at the end of the war, the Army found a card written by T/4 Awald Schulz to his family. No doubt he wrote it under the watchful eye of his captors. On the card, Schulz wrote, “I am well and been feeling fine and have been thinking of you people all the time. I hope to be home by this Christmas…I will see you soon.”

T/4 Awald M. Shulz was lost at age 26. His name is inscribed on the Wall of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines.

Sources

Photo and story details provided by Ms. Jeanie Bowen, T/4 Schulz’s niece.

National Archives: World War II Prisoners of War Data File, 12/7/1941 - 11/19/1946

Air & Space Forces Magazine: Disaster in the Philippines

U.S. Army Center of Military History: Philippine Islands

National Archives: Prologue Magazine—American POWs on Japanese Ships Take a Voyage into Hell

BYU Religious Studies Center: Shinyo Maru

Warfare History Network: U.S. Heavy Bombers in WWII: Caught on the Ground

Texas Co-op Power: Texas Stories—Stellar Allegiance

Honor States: Awald M Schulz

Find a Grave: Tec4 Awald Max Schulz